Casualties and Victim Assistance

Casualties

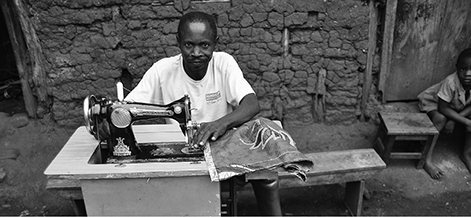

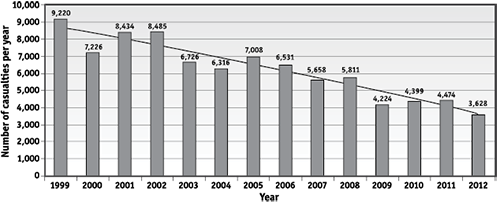

In 2012, recorded casualties caused by mines, victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs), cluster munition remnants,[1] and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)—henceforth: mine/ERW casualties—decreased to the lowest level since 1999. This was the year the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force and the Monitor began tracking casualties. This continued a trend of fewer total annually-recorded mine/ERW casualties that has been fairly steady, with some minor annual aberrations, since 1999. Over the period, annual casualty totals have decreased by more than 60%.

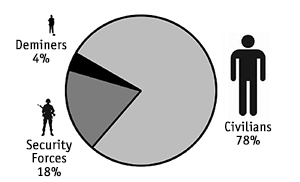

The vast majority of recorded mine/ERW casualties were civilians. They continued to be disproportionally victimized as compared to military and security forces.[2] The percentage of civilian casualties as compared with military casualties increased considerably in 2012 from 2011, up to 78% from 73%.[3] Mine/ERW incidents impact not only the direct casualties—the women, men, boys, and girls who were killed, as well as the survivors—but also their families struggling under new physical, psychological, and economic pressures. In 2012, both child casualties and female casualties increased by a small amount as a percentage of overall casualty totals, compared to 2011 and annual averages in previous years.

Casualties in 2012[4]

In 2012, a total of 3,628 mine/ERW casualties were recorded by the Monitor. At least 1,066 people were killed and another 2,552 people were injured; for 10 casualties it was not known if the person survived the incident.[5] In many states and areas, numerous casualties go unrecorded; therefore, the true casualty figure is likely significantly higher.

The 2012 casualty figure of 3,628 is a 19% decrease compared with the 4,474 casualties recorded in 2011 and 10% fewer than the second lowest casualty total recorded by the Monitor of 4,224, in 2009.[6] In 2012, there was an average of 10 casualties per day, globally, as compared with approximately 11–12 casualties per day from 2009–2011.[7] The annual incidence rate for 2012 is just 40% of what was reported in 1999, when there were approximately 25 casualties each day.[8] Given improvements in data collection over this period, the decrease in casualties is likely even more significant with a higher percentage of casualties now being recorded.

Casualties were identified in 62 states and other areas in 2012,[9] similar to the 61 states and other areas in which casualties were identified in 2011[10] and down from 72 states and other areas the Monitor first recorded for 1999. Of the total casualties in 2012, 2,367 occurred in the 30 States Parties[11] to the Mine Ban Treaty identified by the Monitor as having responsibility for significant numbers of survivors; a total of 2,530 occurred in all (42) States Parties.[12]

Number of mine/ERW casualties per year (1999–2012): Retrospectively adjusted totals

Number of mine/ERW casualties per year (1999–2012): Annual totals as originally reported in the Monitor, unadjusted

For years prior to 2012, the Monitor adjusted global cumulative casualty data retrospectively by adding additional data that had become available[13] and removing past anomalies related to changing data collection techniques and the classification of explosive device types, particularly where there had been unclear differentiation between victim-activated and command-detonated IEDs.[14] Standardizing casualty data from previous years based on the criteria and methodology currently used by the Monitor makes all data since 1999 more consistent for comparison between years and over the whole period, and provides the best possible picture of change during the period. In all years there were estimated to be significantly higher casualties. It is notable that the overall trend in declining casualties is consistent in both the original and the updated data.

Steady declines in annual casualty totals continued in the three States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty that have regularly recorded the highest number of annual casualties over the past 14 years: Afghanistan, Cambodia, and Colombia. Together, these three countries represent 38% of all global casualties since 1999, as recorded by the Monitor. Gradual decreases in the number of casualties in these countries each year have significantly reduced the global casualty figure.

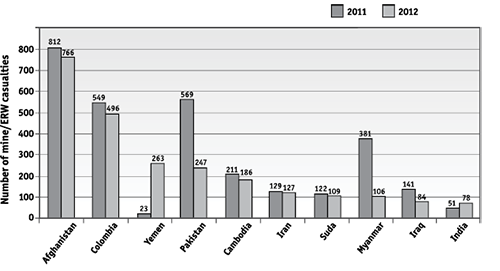

Afghanistan, which has recorded more people directly affected by mine and ERW incidents every year than any other country, had the most annual casualties again in 2012, with 766 people killed and injured. This number was down slightly from the 812 casualties identified in 2011 and was about 90% less than the estimated 9,000 casualties in Afghanistan per year prior to the Mine Ban Treaty. At that time, Afghanistan alone was suffering nearly three times the total global casualty rate in 2012.

Colombia was the second most impacted country, with 496 casualties. The 2012 figure was an 11% decrease compared with the 549 recorded in 2011, and about 60% less than the mine/ERW casualty rate in Colombia when it peaked in 2005 and 2006 at around 1,200 casualties recorded annually.

Cambodia, with the fifth most casualties in 2012, also continued to record fewer casualties than in most previous years: the 186 casualties recorded in 2012 were 13% fewer than the 211 mine/ERW casualties identified in 2011 and more than 90% less than the over 3,000 casualties identified in 1996.

Other significant changes in casualty totals among States Parties in 2012 were mainly due to changing dynamics in relation to armed conflicts. In one of the Mine Ban Treaty’s newest States Parties, South Sudan, mine/ERW casualties dropped from 206 in 2011 to 22 in 2012 as the movement of displaced populations from the north into South Sudan reduced considerably, compared with a peak in casualties just after independence in 2011.

Yemen was the only State Party to the Mine Ban Treaty where there was a significant increase in the number of mine/ERW casualties between 2011 and 2012. At 263, the number of casualties recorded in 2012 was the highest annual number recorded by the Monitor for Yemen since research began in 1999. It was more than 10 times higher than the 23 casualties recorded in 2011 and five times the 52 casualties identified in 2010. This significant increase was due to the increased population movement immediately after fighting subsided in early 2012 and the new use of mines during the armed conflict.

States with 100 or more recorded casualties in 2012

|

State |

No. of casualties |

|

Afghanistan |

766 |

|

Yemen |

263 |

|

Cambodia |

186 |

|

Sudan |

109 |

|

Myanmar |

106 |

Note: States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty indicated in bold.

Among states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, two of the countries with the largest numbers of casualties in previous years, Myanmar and Pakistan, registered significant decreases in the number of casualties identified in 2012 as compared with 2011. There were 247 casualties in Pakistan, down from 569 casualties in 2011, or a decrease of 57%. In Myanmar, the decrease was even more dramatic, down from 381 casualties in 2011 to 106 in 2012, marking a drop of 72%.

However, neither Myanmar nor Pakistan has a data collection mechanism for mine/ERW casualties and the data may be incomplete. The data is taken from media and other local sources that Monitor researchers have available. Both countries have shown large fluctuations in casualty data over the years, due to a combination of the poor quality of available data, real changes in the casualty occurrence rate, and the way casualties were reported due to the dynamics of ongoing conflict. For example, in Pakistan, where the Sustainable Peace and Development Organization (SPADO), a national NGO, collects data via media reports and field workers, recorded casualties tend to decrease when armed conflict prevents journalists and field workers from accessing the very regions of the country where casualties are most likely to occur. Therefore, the reduced number of casualties in both countries should be viewed cautiously and possible discrepancies taken into consideration regarding the global casualty total.

Annual changes (2011–2012) in mine/ERW casualties for the 10 countries with the most casualties in 2012

Libya also saw a significant decrease in casualties, from 226 in 2011 to 66 in 2012. While there was believed to be a decline in mine/ERW casualties, this significant drop is also related to the lack of availability of casualty data for 2012, as compared with 2011.

In 2013, the unprecedented availability of detailed annual and cumulative casualty data over time from Iran, another state not party to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of casualties, made clear the steady decreases in annual casualty totals in that country, following a peak of 918 casualties in 1995. There were 129 casualties in Iran in 2011 and 127 in 2012.

Methodology

The data collected by the Monitor is the most comprehensive and widely-used annual dataset of casualties caused by mines and ERW. For the year 2012, the Monitor collected casualty data from 32 different national or UN mine action centers in 31 states and other areas with mine/ERW casualties during the year. Mine action centers recorded nearly half of the casualties identified during the year.[15] For all other states and areas, the Monitor collected data on casualties from various mine clearance operators and victim assistance service providers, as well as from a range of national and international media sources.[16]

It must be stressed that, as in previous years, the 3,628 mine/ERW casualties identified in 2012 only include recorded casualties. Due to incomplete data collection at the national level, the true casualty total is higher. Based on the updated Monitor research methodology in place since 2009, it is estimated that there are approximately an additional 800–1,000 casualties each year that are not captured in its global mine/ERW casualty statistics, with most occurring in severely affected countries.

As in previous years, data collection in various countries such as Afghanistan, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), India, Iraq, Myanmar, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen was believed to be incomplete due either to the lack of a functioning official data collection system and/or to the challenges posed by ongoing armed conflict. However, the level of underreporting has declined over time as many countries have initiated and improved casualty data collection mechanisms. In addition, for the first time, in 2012, the Monitor received detailed cumulative casualty data from Iran (as noted above).

The 2012 estimate is a significant drop from the estimated total from 1999. By way of comparison, the Monitor identified some 9,000 casualties in 1999, but estimated that another 7,000–13,000 annual casualties went unrecorded.

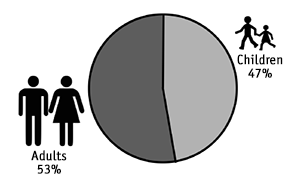

Casualty demographics[17]

Since ICBL monitoring began in 1999, every year there have been about 1,000 child casualties from mines/ERW, with significantly greater numbers of children killed and injured in 1999 and 2001.[18] There were 1,168 child casualties in 2012, an increase from 1,063 in 2011, despite the overall decrease in the global casualty total between the two years. Child casualties in 2012 accounted for 47% of all civilian casualties for whom the age was known.[19] This was an increase of five percentage points from the 42% in 2011 and a slight increase from the average annual rate of child casualties since 2005 of 44%.[20] In some of the states with the greatest numbers of casualties, the percentage was even higher in 2012. Children constituted 72% of all civilian casualties in India;,70% in Somalia, 65% in Sudan, 61% in Afghanistan, and 50% in Yemen.

Mine/ERW casualties by age in 2012[21]

Between 2011 and 2012, significant increases in the number of child casualties were seen in Yemen, Colombia, and Cambodia. In Yemen, where the percentage of child casualties has consistently been high, 105 children were killed or injured by mine/ERW in 2012, seven times the number in 2011 (15). In both Colombia and Cambodia, between 2011 and 2012, the actual number of child casualties increased while the total number of annual casualties decreased, indicating a possible shift in the risk factors related to mine and ERW contamination. In Colombia, there were 66 child casualties in 2012, compared to 44 in 2011, and this represented 30% of all civilian casualties versus 22% in 2011. In Cambodia, the annual number of child casualties increased from 51 to 61 and from 27% to 35% of civilian casualties.

As in previous years, the vast majority of child casualties where the sex was known were boys (80%), while 20% were girls.[22] More than two-thirds of child casualties were caused by ERW. Among casualties of all ages, children were also disproportionately the victims of ERW; 60% of all ERW casualties were children despite ERW being the cause of just 32% of all casualties, with military casualties included.

Child casualties in significantly affected countries, as a percentage of civilian casualties in 2012 [23]

|

Country |

Child casualties |

Total civilian casualties |

Percent of child casualties of Total Civilian Casualties |

|

Afghanistan |

341 |

562 |

61% |

|

Yemen |

105 |

211 |

50% |

|

Colombia |

66 |

217 |

30% |

|

Cambodia |

61 |

176 |

35% |

|

Pakistan |

54 |

168 |

32% |

Note: States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty are indicated in bold.

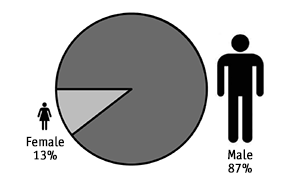

In 2012, the percentage of female casualties among all casualties for which the sex was known was 13%, 410 of 3,183. This was an increase from 2011, when females constituted 10% of all casualties for which sex was known (388 of 3,822).[24] It was also an increase compared to the annual average of 10.5% since 1999, although within the percentage range across this period.[25] As in previous years, the vast majority of casualties where the sex was known were male (87%).

In 2012, the sex of 445 casualties was unknown, or 12% of all registered casualties, down from 15% in 2011 and 2010. The improvement in sex disaggregation was even greater in data provided by national mine action centers: the sex was unknown in just 3% of these casualties in 2012, down from 13% in 2011. This significant improvement in the disaggregation of casualty data by sex is plausible, in part, as a result of calls for improvements in this area by the Mine Ban Treaty’s Cartagena Action Plan.

Mine/ERW casualties by sex in 2012[26]

Between 1999 and 2012, the Monitor identified more than 1,000 deminers who have been killed or injured while undertaking demining operations to ensure the safety of the civilian population.[27] With 132 casualties identified among deminers in 13 states[28] in 2012, this figure was very similar to the number of demining casualties reported to the Monitor in 2011.[29] However, it was significantly higher than the average of 75 casualties among deminers per year since 1999. All casualties of demining accidents in 2012 were men.

In 2012, the highest numbers of casualties among deminers were in Iran (71), Yemen (19), and Afghanistan (16).The 71 deminer casualties in Iran was nearly double the 36 recorded there in 2011; 217 deminer casualties have been identified in Iran since 2008.[30] Demining casualties in Afghanistan decreased by 36% compared between 2011 and 2012. No deminer casualties were identified in Yemen in 2011 and the 19 that occurred in 2012 represented 54% of all demining casualties that have occurred in Yemen since 1999. Together, these three countries represented 80% of all deminer casualties globally. In 2012, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) recorded no deminer casualties for the first year since Monitor reporting began.

Mine/ERW casualties by civilian/military status in 2012[31]

Civilian casualties represented 78% of casualties where the civilian/military status was known (2,763 of 3,564), compared to 73% in 2011. In absolute terms, military casualties decreased by 33% between 2011 and 2012 while civilian casualties decreased by 10%. More than half the drop in military casualties from 2011 to 2012 can be accounted for by decreases in military casualties in just three states—Colombia, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

As in previous years, in 2012 the vast majority (65%) of casualties among military forces were recorded in a small number of countries with ongoing conflict or armed violence: Colombia (270), Pakistan (77), and Afghanistan (77).[32] In 2012, Colombia alone accounted for 42% of all reported global military casualties.

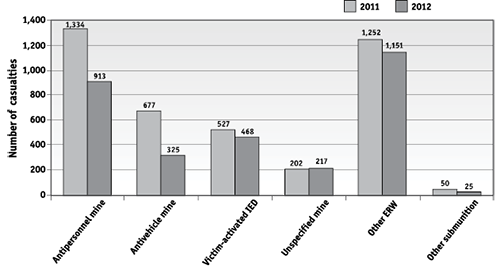

Victim-activated weapons and other explosive items causing casualties

In 2012, 45% of all casualties for which the specific type of victim-activated explosive item was known were caused by factory-made antipersonnel mines (29%) and victim-activated IEDs acting as antipersonnel mines (15%).[33] This was almost the same as the 46% of casualties from antipersonnel mines and victim-activated IEDs recorded in 2011. There was a marginal difference, in that casualties caused by factory-made antipersonnel mines decreased by four percentage points while this was somewhat offset by an increase of two percetnage points in casualties caused by victim-activated IEDs. In 2011, 33% of casualties resulted from antipersonnel mines and 13% from victim-activated IEDs.

States/areas with mine/ERW casualties in 2012

| Africa | Americas | Asia-Pacific | Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia | Middle East and North Africa |

Note: States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty are indicated in bold, other areas in italics.

In 2012, casualties from victim-activated IEDs were identified in 12 states, an increase from the 10 states in all previous years since 2008.[34] Starting in 2008, the Monitor began identifying more casualties from these improvised antipersonnel mines, likely due to both an increase in their use and better data collection that made the distinction more possible to discern both between factory-made antipersonnel mines and victim-activated IEDs and between command-detonated IEDs and victim-activated IEDs.

Casualties by type of explosive device in 2012

* Note: This chart includes only the casualties for which the device type was known.

In 2012, antivehicle mines killed and injured people in 18 states and other areas. The states with greatest numbers of casualties from antivehicle mines were Pakistan (100), Sudan (41), and Niger (40).[35] Between 2011 and 2012, the percentage of casualties caused by antivehicle mines, which are not prohibited or regulated under the Mine Ban Treaty,[36] declined compared to the total, but were similar to levels in 2010. In 2012, 325 casualties, or 10% of casualties for which the device was known, were caused by antivehicle mines, compared with 677 or 17% of casualties in 2011. Antivehicle mines caused 10% of casualties for which the cause was known in 2010.

The sharp increase in antivehicle mine casualties recorded in 2011 had been due, for the most part, to a huge increase as compared to 2010 in just three states—Pakistan, Sudan, and South Sudan. Following this peak, in both Pakistan and South Sudan casualties in 2012 due to antivehicle mines returned to 2010 levels. Antivehicle mine casualties also decreased in Sudan in 2012 as compared to 2011, but still remained high compared to 2010.[37]

In 2012, 37% of casualties were caused by other ERW in 46 states and areas, an increase from 30% in 2011.[38] Some notable increases by country occurred in Yemen, where there were 108 casualties due to ERW in 2012, as compared to just one in 2011. In both Cambodia and Colombia, the total figure of casualties caused by ERW increased while the overall casualty totals per country decreased.[39] The increase in Colombia may be due to enhanced accuracy in the reporting of incidents caused by ERW following awareness-raising efforts in 2012, including by the ICRC, to inform people that legal benefits to victims of explosives were not limited to victims of antipersonnel mines but also included victims of ERW and IEDs.[40]

Victim Assistance

The Mine Ban Treaty is the first disarmament or humanitarian law treaty in which states committed to provide “assistance for the care and rehabilitation, including the social and economic reintegration” to those people harmed.[41]

Since 1999, the Monitor has tracked the provision of victim assistance to landmine and explosive remnants of war (ERW) victims[42] under the Mine Ban Treaty and its subsequent five-year action plans. In practice, victim assistance addresses the overlapping and interconnected needs of persons with disabilities, including survivors of landmines, cluster munitions, ERW, and other weapons, as well as people in their communities with similar requirements for assistance. In addition, some victim assistance efforts reach family members and other people in the communities of those people who have been killed or have suffered trauma, loss, or other harm due to landmines and ERW.

The Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014, agreed upon at the Mine Ban Treaty Second Review Conference in 2009, further developed the concept of victim assistance by combining the various elements of victim assistance into an integrated approach to addressing victims’ needs. This approach stressed the importance of cross-cutting themes, particularly the accessibility of services and information, inclusion and participation of victims, particularly survivors, and the concept that there should be no discrimination against mine/ERW victims, among victims, nor between survivors with disabilities and other persons with disabilities in relation to the assistance provided.[43]

During 2013, with preparations for the Third Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty underway and the time period to implement the Cartagena Action Plan coming to an end, States Parties and other victim assistance actors were taking stock of the progress made and mapping a new course to ensure the fulfillment of victim assistance commitments in the period to follow the upcoming review conference. Monitor reporting since 2009 shows that significant progress has been made as measured against the commitments of the Cartagena Action Plan, particularly in better understanding the needs of mine/ERW victims,[44] coordinating and planning measures to better address those needs, and linking victim assistance coordination with other relevant multisectoral coordination mechanisms. Reporting demonstrates that concerted efforts have been made to make mine/ERW victims more aware of available programs and services and, in some cases, to facilitate their access to these services.

Legal frameworks to promote the rights of victims have improved, including through the regulation of physical accessibility, although discriminatory practices remain in many States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty towards some groups of survivors, or even all survivors, and/or toward other persons with disabilities. In order to address the needs of mine/ERW victims, all States Parties needed to further increase the availability and sustainability of relevant programs and services and ensure that all mine/ERW victims have access to programs that meet their specific needs.

This victim assistance overview focuses on progress under the Cartagena Action Plan since 2009 in the 30 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant

numbers of mine/ERW victims in need of assistance.[45] It also highlights some efforts during the same time period to assist thousands of mine/ERW victims living in states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty that also have significant numbers of victims.[46] Greater detail of progress and challenges in providing effective victim assistance at the national level is available through some 70 individual country profiles available online.[47]

Understanding the needs and challenges of victims

During the period of the Cartagena Action Plan, considerable progress has been made by those States Parties with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims to better understand their needs. Many states also mapped the available services to determine what gaps exist to meet these needs. As of June 2013, 21 of the 30 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of victims had undertaken a complete or partial assessment or survey of the needs of mine/ERW survivors, disaggregated by sex and age. In 10 of these states, needs assessments were underway in 2012 and into 2013;[48] nine other states completed surveys between 2009 and 2011[49] and the remaining two states had carried assessments out prior to 2009.[50] Before the Cartagena Action Plan went into effect, just five of these States Parties had started or completed needs assessments.[51]

Some needs assessments have covered all areas where survivors are registered or known to live. Others have focused on specific geographic areas with high concentrations of survivors or done samplings of the survivor population to extrapolate the needs. In some states, such as Angola, Iraq, South Sudan, and Sudan, needs assessments have been carried out in different regions successively over multiple years. In nearly all cases, surveys have been carried out through a partnership of government agencies and NGOs, including survivor networks and disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs). Exceptions include Serbia, where a national assessment of victims needs was carried out by the NGO Assistance Advocacy Access–Serbia (AAA-S)[52] and requests for government collaboration to provide existing data went unheeded, and Yemen, where ongoing surveys of medical and rehabilitation needs have been carried out by the national mine action center without engaging civil society.

Inclusion of persons with disabilities and victims of armed conflict and violence

The majority of needs assessments since 2009 have surveyed mine/ERW survivors, family members of survivors, persons with disabilities, and/or other victims of armed conflict. Based on available information, “survivor” needs assessments in Algeria, Angola, Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), South Sudan, Sudan, and Uganda all have included both survivors and other persons with disabilities, recording information on the cause of the disability, thus contributing to an improved understanding of the needs of all persons with disabilities in these countries. Other surveys may also have included persons with disabilities when the opportunity arose, but states have not reported on this aspect of the survey within the context of Mine Ban Treaty reporting. In Jordan in 2012, the mine action center surveyed survivors in collaboration with other disability actors to inform disability planning regarding the specific needs of this sub-group of persons with disabilities. In Peru, a pilot project designed to assess the needs of persons with disabilities in order to improve accessibility of services was carried out in a region known to have a significant number of survivors. Needs assessments of mine/ERW survivors in Iraq and Serbia also covered other survivors of armed conflict and explosive violence.

While needs assessments were generally inclusive of survivors and others with similar needs, such as persons with disabilities or victims of armed conflict, few attempts were made to assess the needs of the all people covered under the full definition of victim, including family members of people killed by mines/ERW, family members of survivors, and affected communities. Ongoing collection of data in Albania and the 2012 survey in Mozambique assessed the needs of family members of survivors and those killed. The Mozambique survey also included community members in focus groups. The 2013 village-level survey in Cambodia carried out by the survivor network of the Cambodian Campaign to Ban Landmine, in cooperation with the national mine action center, was an exceptional and exemplary case of a survey that assessed the overall situation in mine/ERW affected communities.

Among states that were not identified as having undertaken needs assessments, in Colombia service providers and NGOs working with survivors reported collecting information on the needs of survivors on an ongoing basis and providing it to the government; however, there was a lack of updated information on the needs of survivors from incidents occurring in previous years. In Nicaragua, a general disability survey was carried out in 2011, including mine/ERW survivors with disabilities. In El Salvador, the Protection Fund for the War Wounded and Disabled (Protection Fund) collected information on the needs of its beneficiaries on an ongoing basis but only for its own program planning. Between 2009 and 2013, Burundi, Chad, and Guinea-Bissau all highlighted the lack of information on the needs of mine/ERW survivors as an obstacle to adequate victim assistance but pointed to insufficient resources as an impediment to carrying out surveys. Work on a national database of persons with disabilities including mine/ERW survivors in Eritrea stalled when UN funding ended in 2011. Ethiopia lacked a needs assessment and information on mine survivors but planned to include mine survivors and other persons with disabilities in its census survey in 2017. No needs assessment was carried out in Turkey.

In the majority of cases, data collected was used to develop victim assistance and/or disability plans or to adjust existing plans and was shared with other victim assistance actors, such as national disability councils, ministries of social protection, and service providers.[53] In Mozambique, data collected in 2012 was to be used in 2013 by the Ministry of Social Affairs to develop a component specific to mine/ERW survivors within the broader disability plan. In Serbia, AAA-S shared results of its survey with the ministry responsible for disability and veterans’ affairs, although no planning process was underway as of September 2013.

Sustainable data collection

Less progress was made in establishing sustainable ongoing mechanisms for data collection, including integrating data in national injury surveillance systems, as called for by the Cartagena Action Plan. As of September 2013, no State Party had fully integrated ongoing casualty and needs assessment data collection into a national surveillance system. In Colombia, this was done in the department of Antioquia in 2009 with plans to expand throughout the country. After delays of close to three years, the process to expand resumed in 2013. In Uganda and Eritrea, efforts began, but were not completed. A pilot project in Eritrea, supported by UNICEF, included data on mine/ERW survivors and was to have been extended nationally, but ended in 2011. In Sudan, a national health surveillance system that was to include data related to mine/ERW survivors was underway as of May 2013.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and Croatia, data was to be integrated into injury surveillance systems but plans were never implemented. In Albania, an ongoing mechanism was established to collect information on the needs and services received of both survivors and family members. However, the system was maintained by a national NGO that struggled to secure sufficient funding to continue operating. In seven other States Parties, data on the needs of mine/ERW victims (or at least survivors) was shared with disability councils or other relevant ministries, but not specifically as part of an ongoing surveillance system.[54] In at least 10 other States Parties where needs were assessed—nearly half of all states having collected data—no ongoing, sustainable mechanism was established to maintain and manage data on mine/ERW victims’ needs.[55]

Coordination and planning

By the start of the Cartagena Action Plan in 2009, many states with significant numbers of victims had already established victim assistance focal points and multisectoral victim assistance coordination mechanisms. Progress in this area continued under the Cartagena Action Plan as more coordination mechanisms were formed and fewer of these mechanisms relied on UN assistance to operate.

The review of progress in achieving victim assistance under the Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009 found that “the most identifiable gains have been process-related,” referring to coordination and planning.[56] Between 2005 and 2009, 12 states developed interministerial coordination mechanisms to implement action plans, six of which were supported by UN mine action centers or advisors.[57] However, in 2009 the Monitor found that these mechanisms were not functioning in at least 50% of these countries.[58]

As of June 2013, nearly all of the 30 States Parties with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims had a victim assistance focal point.[59] The number of states with multisectoral coordination for victim assistance and/or inclusion of mine/ERW victims (such as coordination for persons with disabilities or victims of armed conflict) had increased to 22.[60] In addition, fewer States Parties, down to three from six, were reliant on the UN to support victim assistance coordination.[61]

However, in several cases effective coordination was not continuously sustained by national actors throughout the period. In 2012, victim assistance coordination in Croatia was temporarily suspended during administrative reorganization following national elections. In Uganda, coordination meetings were less frequent than in other recent years due to reduced international support. Victim assistance coordination mechanisms were inactive in Algeria, Chad, and Yemen in 2012.

Among the eight[62] States Parties without multisectoral coordination, El Salvador’s Protection Fund for the victims of armed conflict coordinated victim assistance but without regular coordination with other government ministries. In Iraq, there was a functioning regional multisectoral coordination mechanism in the region of Kurdistan, chaired by the Kurdistan mine action centre and supported by UNDP, but no coordination mechanism for the rest of the country.

Coordination of victim assistance through or in coordination with other relevant frameworks in 2012

Since 2009, victim assistance has increasingly been coordinated by disability ministries or councils, rather than by mine action centers. Coordination of victim assistance in many States Parties has been combined with disability coordination, or greater collaboration has emerged between these two sectoral coordinating mechanisms.

In 12 of 30 States Parties with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims, the victim assistance focal point was the ministry responsible for disabilities issues. In at least three of these States Parties, this marked a change since 2009 from a victim assistance focal point based at a mine action center.[63] However, in all three of these States Parties, the mine action centers remained critical in supporting the ministries responsible for disability issues in this new role.[64] In Serbia, the victim assistance focal point changed from the national rehabilitation center to the Ministry of Social Policy, marking an important shift from a medical focus for victim assistance to a social approach.

Among the 21 States Parties with active victim assistance coordination mechanisms, all but two (El Salvador and Senegal) were either combined with disability coordination mechanisms (seven plus Darfur) or there was collaboration across the two coordination mechanisms (12 plus Iraqi Kurdistan).[65] In countries such as Afghanistan, Cambodia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Tajikistan, disability coordination mechanisms grew out of victim assistance coordination, adding the coordination of disability issues to their existing victim assistance mandate. Such collaboration in these countries was inherent from the start.

Since 2009, victim assistance coordination has been increasingly integrated with what, in many cases, are emerging disability coordination mechanisms, yet this has not been effective in all cases in improving coordination overall or in ensuring greater integration of survivors within the disability community or among the beneficiaries of programs targeting persons with disabilities. In 2012, BiH’s victim assistance focal point, based at the mine action center, had limited coordination with relevant disability actors. In Colombia, coordination between victim assistance and disability sectors was not effective in integrating mine/ERW survivors into government efforts to address issues of disability. In DRC, while there was victim assistance and disability collaboration, both coordination mechanisms were irregular, ineffective, and dependent on international technical assistance. In Mozambique, coordination by the national disability council, into which victim assistance coordination was integrated, was found to be weak, under-resourced, and largely ineffective, with little impact on the lives of persons with disabilities.

Victim assistance coordination was also linked to efforts to coordinate and implement national policies to compensate, rehabilitate, and/or provide reparations to armed conflict victims, including victims of mines and ERW, in at least 13 States Parties.[66] In many cases, these policies, sometimes referred to as transitional justice or “victims’ laws,” explicitly included efforts to address the needs of mine/ERW victims. In five states, policies were limited to military victims (either disabled veterans or the families of those killed).[67] In Colombia and El Salvador, laws for victims of armed conflict require comprehensive rehabilitation for both civilian and military victims, including family members of people killed. In Turkey, some victims could apply to receive a one-time payment under laws dedicated to compensating victims of terrorism or counter-terrorism. Mine survivors in Thailand could receive a one-time compensatory payment immediately after injury. In Peru, in theory, the program to provide reparations to victims of armed violence included victims of landmines but, in practice, bureaucratic procedures made it nearly impossible for victims to access assistance through this program.

In Colombia, in 2012 mine/ERW victim assistance coordination was largely replaced by the coordination mechanism for the implementation of the country’s law of reparations for all victims of armed conflict. While some saw this as a more effective way to coordinate victim assistance, for others the shift raised concerns that the specific needs of mine/ERW survivors might be lost within the much larger group of armed conflict victims with divergent needs, such as displaced persons.

Victim assistance (VA) and disability coordination, 2012

|

Mine Ban Treaty State Party with significant numbers of victims |

Common Focal Points |

Collaboration between or Combined VA |

|

Afghanistan |

Yes |

Combined |

|

Albania |

No |

Collaboration |

|

Algeria |

No |

No VA coordination mechanism |

|

Angola |

No |

Collaboration |

|

BiH |

No |

Limited collaboration |

|

Burundi |

No |

Collaboration |

|

Cambodia |

Yes |

Combined |

|

Chad |

No |

No VA coordination mechanism |

|

Colombia |

No |

Collaboration |

|

DRC |

Yes |

Collaboration |

|

Croatia |

No |

No VA coordination mechanism |

|

El Salvador |

No |

None |

|

Eritrea |

Yes |

Combined |

|

Ethiopia |

Yes |

Combined |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

No |

Collaboration |

|

Iraq |

No |

No VA coordination mechanism; collaboration in Kurdistan |

|

Jordan |

Yes |

Collaboration |

|

Mozambique |

Yes |

Combined |

|

Nicaragua |

N/A |

No VA coordination mechanism |

|

Peru |

No |

Collaboration |

|

Senegal |

No |

Unknown |

|

Serbia |

Yes |

No VA coordination mechanism |

|

Somalia |

N/A |

No VA coordination mechanism |

|

South Sudan |

Yes |

Combined |

|

Sudan |

No; Darfur- Yes |

Collaboration; combined in Darfur |

|

Tajikistan |

No |

Collaboration |

|

Thailand |

Yes |

Collaboration |

|

Turkey |

Yes |

No VA coordination mechanism |

|

Uganda |

Yes |

Combined |

|

Yemen |

No |

No VA coordination mechanism |

Note: Bold in the second column indicates a change in the VA focal point since 2009; Yes=states where the focal point is the same person; No=VA focal point is not the same as the disability focal point; N/A=states with no VA focal point. In the third column, collaboration=two different mechanisms work together; combined=same mechanism for VA and disability coordination; none=there is no collaboration between VA and disability coordination. It is possible to have a focal point without a coordination mechanism.

Planning

The Cartagena Action Plan calls on States Parties to develop and implement a comprehensive plan of action, with a budget, to meet the needs and human rights of mine victims, including by ensuring that broader relevant national policies, plans, and legal frameworks take account of mine victims. Between 2005 and 2009, under the Nairobi Action Plan, 10 states[68] with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims had already developed victim assistance plans and seven[69] of these were actively being implemented in 2009.

By 2013, more than three-quarters of the States Parties with significant numbers of victims had a victim assistance plan of action or a broader plan that included victims, or were in the process of developing such a plan.[70] Nineteen of 30[71] had an approved plan in place, and of these, seven were new in 2012.[72] An additional four states had plans under development. Afghanistan and Angola were developing victim assistance plans to replace previous plans that had expired while Algeria and Guinea-Bissau were developing their first victim assistance plans.

However, while many states made considerable efforts and received international support to develop plans aligned with the Cartagena Action Plan, and in several cases also aligned with victim assistance obligations under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, progress in implementing plans was limited in many states. Plans in Croatia and Yemen[73] were inactive in 2012. In Burundi, Chad, Mozambique, and Uganda, a lack of dedicated funding prevented the implementation of plans. The victim assistance plan in BiH lacked clearly defined responsibilities and was reported to be ineffective as a tool to support adequate victim assistance. In DRC and South Sudan, reduced funding for victim assistance halfway through 2012 greatly slowed progress in implementing these plans.

Planning through, or with, other relevant frameworks

In 2012, in a growing number of States Parties victim assistance planning was integrated into broader frameworks, most especially disability planning and/or plans to address the rights and rehabilitation of victims of armed conflict.

In six states, mine/ERW survivors or their representative organizations were explicitly included in the national disability plan and/or its development.[74] For example, Mozambique’s disability plan for 2012 to 2019 includes a specific section related to assistance for landmine survivors with the objective to “[p]rovide psychosocial support and socioeconomic reintegration for mine victims with disabilities.” The section included a budget for its implementation but lacked dedicated funding. In two additional states, Algeria and South Sudan, disability plans were under development as of June 2013 that included mine/ERW survivors.

Several states had both victim assistance and disability plans that were developed to be complementary and mutually reinforcing. For example, Albania’s victim assistance plan referred to the national disability plan and South Sudan’s victim assistance plan included efforts to promote the ratification of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) for the benefit of survivors and other persons with disabilities. Burundi’s victim assistance plan contained actions to promote the rights of all persons with disabilities. In Peru, the annual victim assistance work plan included a component to assist survivors in registering as persons with disabilities in order to access benefits available to that population. Ethiopia adopted a national disability plan in 2012 that it also intended to apply to victim assistance efforts.

Guinea-Bissau lacked a specific national plan on victim assistance in 2012; however, its National Poverty Reduction Strategy 2011–2015 includes the aim of the “rehabilitation and reintegration of all victims (victims of war and mines/ERW included) and their full participation in the socio-economic reconstruction to [sic] the country as an actor for development, and thus re-establish their rights and dignity.” In 2012, Colombia approved a national plan for the implementation of its victims’ law. In Uganda, the perspective of survivors was included in planning national community-based rehabilitation efforts.

Monitoring, evaluation, and reporting

While several victim assistance coordination mechanisms included the monitoring of the implementation of victim assistance plans within their mandate, little information was available on an annual basis on the results of such monitoring. In 2011, Mozambique undertook a comprehensive evaluation of the results of the national disability plan at the plan’s conclusion, and Angola made a similar effort in 2012 after its victim assistance plan expired. In Uganda, a tool to monitor the implementation of the national victim assistance plan was developed and piloted in 2012. A full evaluation of the plan was programmed for early 2014. An evaluation of Senegal’s victim assistance plan was underway as of May 2013.

Experts from States Parties noted that most existing victim assistance plans (and disability plans that included victim assistance) lacked functioning monitoring mechanisms, and requested training on monitoring and evaluation. The Mine Ban Treaty’s sessions of the Victim Assistance Experts’ Parallel Programme in May and December 2012 were dedicated to improving these technical skills.[75]

Between 2009 and 2013, most States Parties with significant numbers of victims regularly reported on their efforts to implement victim assistance, either through statements at meetings of States Parties or through completion of the voluntary form J of the Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 reports, or both. In 2012, all but three of the 30 States Parties with significant numbers of victims provided reporting in some form.[76] Only South Sudan directly linked its reporting through the Article 7 report to its planning process, providing its victim assistance plan as an annex to the report. Several states gave detailed reports on progress and challenges in implementing victim assistance, including Afghanistan, Albania, Colombia, Eritrea, and Tajikistan. Mozambique provided detailed reporting on victim assistance through its Article 7 reporting under the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Guinea-Bissau reported on efforts to assist victims through the national poverty reduction strategy. Reporting from BiH declined over the period, and in 2012/2013 little reporting was made available.

Survivor inclusion and participation

In assessing progress under the Nairobi Action Plan in 2009, the Monitor found that “few Mine Ban Treaty States Parties have fulfilled their commitment to involve survivors in planning, implementation, and monitoring of VA [victim assistance] activities at local, national, regional or international levels.”[77] In contrast, as of 2013, 18 of 21 States Parties with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims and active coordinating mechanisms for victim assistance involved survivors or their representative organizations in those mechanisms. Survivors were also actively involved in the implementation of victim assistance in nearly all States Parties, although most often as staff or board members of NGOs, including survivor networks.

In 18 of 30 States Parties with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims, survivors participated in victim assistance coordination or in the coordination of other relevant frameworks.[78] In all but four of the 18, representation was organized through national or local survivor networks.[79] In Sudan, where there was no specific survivor network, survivors were represented in both the national victim assistance coordination mechanism and the national disability council through DPOs that included survivors.

Even where there was no regular victim assistance coordination, in a further three States Parties, survivors who were organized in groups and networks found opportunities to present and have their views included in victim assistance-related programs and plans in 2012. In Serbia, where there was no active victim assistance coordination, survivors and their representative organizations included themselves in other relevant spaces, such as committees to revise the law on veterans with disabilities and to reform regulations requiring accessibility for all to buildings and public spaces. The national network of survivors in El Salvador coordinated regularly with the Protection Fund for victims of armed conflict. In Iraq, the national alliance of persons with disabilities, an organization led by a survivor, met with representatives of the mine action center and ministry of social affairs regularly.

While survivor participation in national victim assistance coordination increased under the Cartagena Action Plan, it was not always effective in terms of the ability of survivors to contribute to decision-making, often due to a lack of resources. The vast majority of survivor networks had very small or no budgets and were dependent on small amounts of international financial support and/or voluntary contributions of time and in-kind support from their members. This restricted the ability of many networks to maintain regular contact with members in order to properly represent their views and needs, as well as to cover travel costs to participate in coordination meetings, which government representatives in Colombia noted, for example.

In some cases, a lack of financial support forced survivor networks to close down during the period of the Cartagena Action Plan, such as in Ethiopia, Jordan, Peru, and Serbia. The closure of the international NGO Survivor Corps (formerly Landmine Survivor Network) in 2010 eliminated an important source of financial and technical support for survivor networks. Between 1997 and 2010, Survivor Corps supported and/or organized survivor networks in some 20 different mine-affected countries, championing survivor-led advocacy and peer support among survivors. The launch of the ICBL-CMC’s Survivor Network Project in 2012 at least partially began to fill the gap created by the closure of Survivor Corps and to meet civil society’s demand for support of survivor participation. By mid-2013, it had provided financial support to 11 survivor networks in as many countries.

Overall, national government support for survivor networks was limited, although at least 10 States Parties did provide support of some kind to survivor networks or disabled veteran organizations between 2009 and 2013.[80] Generally, the support was in-kind or in the form of training and capacity-building. For example, in Tajikistan, the national mine action center strengthened the capacity of emerging networks and helped link the networks with international financial assistance. Local authorities provided the survivor network with spaces for meetings and training courses. In Colombia, the Medellin City Council trained local survivor associations in providing psychological support in 2011 and the national mine action center launched a survivor network capacity building project in 2012. In South Sudan, the Ministry of Social Affairs supported the formation of a survivor network and included it in training for other DPOs. In Thailand, the government facilitated the participation of survivor groups in meetings and in conducting outreach.

Between 2009 and 2013, survivors and survivor networks were also active in implementing victim assistance in at least 23 States Parties.[81] Survivors, through survivor networks, were most often active in peer support, including raising awareness of services and providing transportation, social inclusion, and advocacy on survivors’ rights. In several states they were also active in the fields of physical rehabilitation and economic inclusion.[82] Survivors and survivor networks also had a key role in monitoring national victim assistance implementation for Monitor reporting. Between 2009 and 2013, survivors or survivor networks from 10 States Parties formed part of the Monitor research network, investigating all aspects of victim assistance coordination and implementation.[83]

Less progress was seen between 2009 and 2013 by States Parties in the participation of survivors at international levels, either through their involvement in preparing statements on victim assistance for international meetings of the Mine Ban Treaty or through their direct participation in these meetings as members of states’ delegations. In 2009, seven States Parties included a survivor or person with a disability as a member of their delegation at intersessional meetings and/or the review conference. For the entire period from 2010 to 2013, the Monitor identified just six States Parties with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims with a survivor or person with a disability as a member of their delegation.[84]

In just five other States Parties, survivors contributed in other ways to the work of their states’ international representation under the time period of the Cartagena Action Plan. Survivors from El Salvador, Ethiopia, and Tajikistan contributed to the drafting of national victim assistance statements prior to some international meetings. Uganda’s government victim assistance focal point shared statements prepared for international meetings with survivors’ representatives prior to the meetings. In Cambodia, survivors were involved in the organization of the Eleventh Meeting of States Parties in their country.

Survivor participation in other frameworks

In addition to their participation in victim assistance coordination and implementation, several survivors and their representative organizations participated in other forums and frameworks. In 11 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, survivor networks were actively involved in efforts to join and/or implement the CRPD.[85] In Afghanistan, Albania, DRC, and Iraq, survivors along with other DPOs were successful in advocating for ratification of the CRPD in 2012 and 2013. In BiH, Cambodia, El Salvador, Mozambique, Peru, and Uganda, survivors and their representative groups supported effective implementation of the CRPD, including through the development of an implementation plan (in Peru), assessing the needs of persons with disabilities and monitoring the CRPD’s implementation (in BiH and El Salvador), and raising awareness of rights of persons with disabilities and obligations of national and local authorities under the CRPD (in Cambodia, Mozambique, and Uganda).

In several cases, work on the CRPD or efforts to promote disability rights more generally was facilitated by increased collaboration between survivor networks and DPOs over the last five years. In Albania, Algeria, BiH, Burundi, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Senegal, and Thailand, survivor networks worked with DPOs, in most cases around CRPD implementation and ratification campaigns. In Algeria and Mozambique, the survivor network and DPOs worked together to implement needs assessments and service referral programs. In El Salvador, the survivor network participated in a national coalition of DPOs that drafted El Salvador’s alternative report on CRPD implementation. In Senegal’s Casamance region, the local survivor network shared office space with a DPO. Despite generally improved and increased collaboration among survivor networks and DPOs, some survivor networks, including in Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Uganda, reported resistance to their participation in the national disability rights movement on the part of DPOs, particularly national federations of DPOs.

At the provincial and local levels, survivor groups were also active through a range of different frameworks in several States Parties. In BiH, El Salvador, and Serbia, survivor groups worked with local authorities to promote physical accessibility to buildings and public spaces. Regional committees for the implementation of the Victims’ Law in Colombia included representatives of survivor groups. In Thailand, an increasing number of survivors held leadership roles in their communities. In Uganda, a local survivor group was elected to serve on a committee responsible for the design and implementation of local development projects.

Service accessibility and availability

The Cartagena Action Plan calls on States Parties to increase the availability of and accessibility to appropriate services for mine/ERW victims while also raising awareness among mine/ERW victims and within government authorities about available services. Following the Nairobi Action Plan, it was determined that there remained a particular lack of opportunities available to victims for psychological support and economic inclusion, while many victims in rural and remote areas still struggled to access all types of assistance, including healthcare and rehabilitation.

Under the Cartagena Action Plan, some progress was made in increasing awareness of available services, although by 2013 there remained a need to facilitate access to services and programs for most mine/ERW victims. Availability of services increased during the period in some States Parties, but mostly in the area of physical rehabilitation as funding targeted for victim assistance supported the opening of new rehabilitation centers in regions of mine-affected countries where there were significant numbers of mine/ERW survivors.

However, in other States Parties, the availability of victim assistance decreased as international support declined, underscoring the continued importance of finding solutions to sustain programs that benefit survivors along with other persons with disabilities. As of September 2013, several national NGOs promoting and providing a range of assistance, including social and economic inclusion and psychological support, were reporting funding shortfalls that could result in their closure unless immediate funding was secured.

Access to victim assistance

Between 2009 and 2013, there have been important efforts in 17 of the 30 States Parties with the most significant numbers of mine/ERW victims to increase access to mainstream services and programs by making survivors aware of available services through service directories and referrals.[86] In Colombia and Sudan, mine action centers have produced directories of victim assistance. Handicap International (HI) has done the same in Algeria, DRC, Iraq, Mozambique, and Uganda, working with local survivor networks and DPOs in the production and distribution of the directories. In various States Parties where the ICRC or the ICRC Special Fund for the Disabled operates, the ICRC has established referral networks, often in cooperation with the local Red Cross or Red Crescent, to make survivors and other persons with disabilities more aware of rehabilitation programs.

In 11 of the 17 States Parties, survivor networks and other DPOs have continuously referred survivors to services as a component of peer support (BiH, DRC, El Salvador, Senegal, Thailand, Uganda, and Yemen) and/or while undertaking needs assessments (Cambodia, Mozambique, Serbia, Senegal, and Sudan).

In 2012, programs to facilitate access to victim assistance decreased in Colombia and Uganda as international funding and support to victim assistance actors in both countries declined. In these states, various NGOs have supported access by funding transportation and accommodation and paying for services on behalf of survivors who would have been unable to reach services otherwise.

Improvements in physical accessibility in several countries, due to an increase in accessibility laws and regulations (see below), have made some services, particularly health centers and schools, more accessible to mine/ERW survivors since 2009. However, improvements have been modest to date and have largely been limited to urban centers, while most survivors are based in rural areas.

Availability of victim assistance

In 2012, increases in the availability of services for mine/ERW survivors were identified in eight States Parties.[87] Colombia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Jordan, and Nicaragua, all saw an increase in physical rehabilitation centers with new centers in Colombia, Jordan, and Nicaragua located in parts of the country where there were significant numbers of mine/ERW survivors. In El Salvador, the annual budget of the Protection Fund increased in 2012, making physical rehabilitation services and economic inclusion opportunities, including pensions, available to a larger group of mine/ERW survivors and other victims of armed conflict. In Nicaragua and Peru, there were increased opportunities for economic inclusion through victim assistance projects that also benefited other persons with disabilities. The community-based rehabilitation program in Thailand expanded, reaching more survivors in remote and rural areas. In Yemen, the increased availability of assistance was a result of the restarting of the mine action center’s victim assistance program following its suspension in 2011.

At the same time, availability of services decreased in nine other States Parties, either due to reduced international assistance (including both funding to or technical support from international NGOs) or decreased national investment in physical rehabilitation.[88] In Cambodia, DRC, Eritrea, South Sudan, and Uganda, international dedicated victim assistance support—either through the UN or international NGOs—decreased or was suspended, thus reducing the number of economic inclusion projects that targeted mine/ERW victims and also benefited other persons with disabilities. In Angola, Mozambique, and Senegal, prosthetic production declined or ceased altogether in 2012. In Angola, the availability of physical rehabilitation declined through the period, following the transition of rehabilitation centers to national management. In Mozambique, there were no prosthetics produced from mid-2011 through early 2013 due to a lack of materials. In Senegal’s Casamance region, a lack of trained technicians forced the rehabilitation center to suspend production until the center could be properly staffed.

International legislation and policies

The Cartagena Action Plan calls for a holistic and integrated approach to victim assistance that is sensitive to both age and gender, as well as being undertaken in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law. The Cartagena Action Plan refers to the need for “adequate” assistance, without defining what adequate means. Relevant international humanitarian and human rights law should guide States Parties on the scope of their responsibilities and must in any case be applied by those countries that are party to the relevant conventions and treaties. For example, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) clearly recognizes the right “to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of pnhysical and mental health.”[89] Similar applicable provisions with specific age and gender focus, respectively, are found in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).[90]

Other international instruments with close relevance to victim assistance that may be used synergistically with the Mine Ban Treaty include the CRPD, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, Protocol V of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW), and the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.[91]

The right to equality and non-discrimination

States Parties have committed not to discriminate in the provision of assistance either against or among mine victims and also not to discriminate between mine survivors with disabilities and other persons with disabilities.[92] However, between 2009 and 2013, some types of discrimination persisted in many different States Parties.

In some States Parties, national organizations of persons with disabilities were part of intersectoral decision-making bodies or had influence over the distribution of states resources designated for assisting persons with disabilities, while local mine survivors’ organizations were not able to attain the same access, for example in Croatia and Ethiopia. In Uganda, the national mine survivor network struggled for acceptance by the national disability federation for several years before finally gaining a non-voting seat in mid-2013. In Albania, certain groups of persons with disabilities had benefits and privileges for themselves and their families which were not available to landmine survivors with disabilities. Conversely, facilities and services established through the victim assistance program in Albania were available to all persons with needs similar to those of mine/ERW survivors.

War veterans, including injured war veterans and former combatants with disabilities from mine/ERW and other causes, received greater services and benefits than civilian survivors in many countries, including in Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, Eritrea, Senegal, Serbia, and Thailand. Jordan reported having made efforts to redress the preferential treatment of military survivors by increasing victim assistance available to civilians.

In some States Parties both military and civilian war victims received privileged or different treatment. In Colombia and in El Salvador, certain benefits were available to all registered conflict victims, including both civilian and military mine/ERW survivors, which were not available to other persons with disabilities. In September 2013, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities called on El Salvador to develop a system of social protections for all persons with disabilities similar to what was available for persons with disabilities as a result of armed conflict.[93]

The rights of the children[94]

Many survivors are children, especially boys, yet age-sensitive assistance has remained one of the least considered aspects of the victim assistance activities under the Mine Ban Treaty. Children whose injuries result in amputated limbs require more complicated rehabilitative assistance; they need to have prostheses made more often as they grow and may require corrective surgery for the changing shape of a residual limb (stump).[95]

In many countries, child survivors have to end their education prematurely due to the period of recovery needed and the accompanying financial burden of rehabilitation on families. A lack of physical access to schooling and other public services essential to social and economic inclusion was an ongoing challenge for child survivors in many countries. Access to education was often further hindered by the lack of appropriate training for teachers.

Most efforts reported by states to address the needs of child victims have been limited to disaggregating data on survivors, not on their efforts to address the specific needs of all child victims according to their age. Victim assistance providers rarely keep statistics that provide reliable records of how many child mine/ERW survivors or other children with disabilities have been assisted and which services have been rendered. Where age-sensitive assistance were present, most reported services were for child survivors, although children of people killed were covered by laws on victims of armed conflict in Colombia and El Salvador.

Recognizing the need for improvements in the area of victim assistance for children, the Co-Chairs of the Mine Ban Treaty Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-economic Reintegration initiated a process to develop international guidelines on providing assistance to children, adolescents, and their families. The process began with a two-day workshop of victim assistance experts in May 2013. This coincided with efforts by UNICEF in 2013; the theme of its flagship report “The State of the World’s Children” was children with disabilities and included a focus on the impact of mines/ERW.[96]

Since 2009, efforts to assist children or make their rights available have been isolated and sometimes cursory. In 2012 and 2013, an increasing, although small, number of activities to address the specific needs of survivors according to their age were reported in States Parties. These developments included progress in several countries, but also recognition of the remaining and ongoing challenges in most States Parties with responsibilities for child victims.

In Colombia, most hospitals were able to provide emergency medical care specific to the needs of child survivors, but access to appropriate ongoing medical care was hampered by administrative and bureaucratic obstacles. Child survivors in rural areas faced a scarcity of school transportation and schools themselves were not adapted to the needs of children with disabilities. In response to a significant increase in child casualties in 2011 and 2012, Colombia established a special coordination committee for child victims.

The Regional Center for Psychosocial Rehabilitation of Children and Young People, Including Mine Victims, “Model of Active Rehabilitation and Education (M.A.R.E),” was successfully established in Croatia by mid-2012.

In Uganda, a government-launched program on inclusive education and a national accessibility campaign contributed to some increased access to schools for children with disabilities, although this was mainly limited to urban areas.

Since 2008, a government-run inclusive education program has been operating in Afghanistan that increased the enrollment of children with disabilities. Inclusive education training for teachers, as well as children with disabilities and their parents, continued to increase in 2012.

In South Sudan, a school for children with disabilities opened in 2012; however, there was a lack of teachers trained in working with children with disabilities. In Senegal, there was an increased focus on education for child survivors. In Yemen, some schools were made physically accessible in the reporting period.

Gender-sensitive victim assistance and the rights of female victims

In considering what constitutes a rights-based approach to gender-sensitive victim assistance, CEDAW includes relevant provisions on rights of women to health, education, employment, and economic and social benefits on an equal basis with others; it also includes provisions for States Parties to take all appropriate measures to ensure the application of the convention to women in rural areas.[97]

However, similar to the situation of age-sensitive victim assistance, most efforts reported over the last five years regarding gender have been in the disaggregation of casualty data and assessment survey information. Addressing the needs of female survivors and female family of men or children killed and injured by mines/ERW has received far less attention in reporting by states and service providers. Yet, several specific activities were recorded in 2012 and there has been an overall increase in such activities being reported since 2009.

The Swedish Committee for Afghanistan (SCA-RAD) increased the number of beneficiaries of its services in Afghanistan, including the number of women provided with transportation and accommodation at their facilities with an outreach program and mobile orthopedic workshop.

In Algeria, HI expanded its programs for mine/ERW survivors and other persons with disabilities to increase access to the labor market for youth and women with disabilities. In Burundi and El Salvador, there were increased economic inclusion opportunities for women mine/ERW survivors than there had been in previous years. The Yemen Landmine Survivors’ Association increased the participation of women and girl mine/ERW survivors in its peer support and economic and advocacy activities in 2012.

Some organizations working with mine/ERW victims particularly addressed the needs of women. In South Sudan, the national NGO Christian Women’s Empowerment Program provided vocational training and income-generating activities for women. In Uganda, a local DPO, Kasese District Women with Disabilities, provided ongoing support to members through advocacy and referral to physical rehabilitation.

In Mozambique, an evaluation found that, despite the efforts of many programs for persons with disabilities to promote the inclusion of women with disabilities, women with disabilities still suffered greater discrimination than men with disabilities, with more living in poverty and experiencing lower rates of employment. This situation is far from exceptional and similar findings from other countries were presented periodically in surveys since 2009.

Recent surveys for Europe and central Asia in 2012[98] and Cambodia in early 2013[99] also demonstrated that women with disabilities in countries with mine/ERW survivors faced multiple forms of discrimination.

Often, where assistance existed, the focus was on survivors who are predominately male. Few instances have been reported of fulfillment of the rights to assistance for family members who are often female heads of households and who often have the greatest responsibility for the care and assistance of child survivors. An area where this differs to some extent is under laws for veterans and victims of violence and armed conflict. Women who have lost their husbands are entitled to receive some benefits in countries, including Afghanistan, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, and others. In Iraq, the ICRC provided assistance to register for benefits and supported income-generating activities for thousands of female heads of households whose spouses were victims of conflict, including due to mines/ERW.

Regulation of the right to physical accessibility

Physical accessibility to healthcare, education, job training programs, other public services, and community spaces can be a first step toward broader accessibility to services for mine/ERW survivors. Through the Cartagena Action Plan, States Parties committed to increasing accessibility to appropriate services by removing barriers, by the application of relevant standards and accessibility guidelines, as well as by the application of good practices. To this end it was recommended that states assess the accessibility of the physical environment and adapt inaccessible construction to be fully accessible, based on international standards.[100]

The CRPD also recognizes the importance of accessibility, including access to the physical environment, in enabling persons with disabilities to fully enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms. The Monitor found that as of mid-2013, many States Parties still lacked laws or standards on physical accessibility, and several states that had such legislation were not implementing it.

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The CRPD is an international human rights convention that recognizes the dignity and human rights of persons with disabilities, not by creating new rights, but rather by identifying existing human rights and providing for the implementation of those rights.[101] In the Mine Ban Treaty context, the CRPD is considered to “provide the States Parties with a more systematic, sustainable, gender sensitive and human rights based approach by bringing victim assistance into the broader context of persons with disabilities.”[102]

The ICBL has noted that synergies between victim assistance obligations and CRPD obligations require efforts on both fronts in order for survivors and other persons with disabilities to benefit to the greatest extent possible. The ICBL also has cautioned that the mainstreaming of victim assistance within the broader field of disability without championing assistance for mine/ERW victims who are not persons with disabilities will likely lead to some victim assistance obligations not being fulfilled.[103]

In June 2013, Thailand, Co-Chair of the Standing Committee on Resources, Cooperation, and Assistance, hosted the Bangkok Symposium on Cooperation and Assistance: Building Synergy Towards Effective Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Implementation. The event had a particular focus on victim assistance, disability rights, and development. The ICBL noted that victim assistance cooperation resources must be understood to be those that actually reach the victims. The ICBL highlighted a need to continue supporting dedicated victim assistance activities, including survivors’ own networks, while monitoring the impact of support that may reach survivors through other frameworks.[104]

The Cartagena Action Plan often refers to a rights-based approach to assistance. As mentioned above, several states have referred to the ratification and implementation of the CRPD as part of victim assistance activities and sometimes as a concrete objective of their victim assistance planning. The efforts of victim assistance actors, including survivor networks in many States Parties, have contributed to national advocacy efforts around the CRPD.